Taste is the new Meta

The setup

I wrote recently about how AI collapses the cost of experimentation. The cost of building things has dropped dramatically. Ideas that used to take weeks to prototype now take hours.

The immediate reaction from a lot of people has been: “taste is the new differentiator.” If anyone can build, the person who knows what to build wins.

They’re half right. Taste is the differentiator. But it was always the differentiator. AI didn’t create the gap between people with taste and people without it. AI just made the gap impossible to ignore.

Jobs knew this in 1995

Steve Jobs said this in a 1995 interview, a full decade before the iPhone:

“Ultimately, it comes down to taste. It comes down to trying to expose yourself to the best things that humans have done and then try to bring those things into what you’re doing.”

And later:

“Your taste gets more refined as you make mistakes.”

Two things worth noting. First, taste isn’t aesthetics. It’s not about making things pretty. It’s about knowing what to include and, more importantly, what to leave out. Every product decision is a filtering decision. Taste is the quality of the filter.

Second, you develop taste by getting things wrong. Not by reading about getting things wrong. By actually shipping something, watching it fail, and understanding why. There’s no shortcut for that. The knowledge comes from the scar tissue.

Jobs and Ive

When Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, the company was 90 days from bankruptcy and shipping dozens of unfocused products. One of his first acts was killing 70% of the product line. That’s taste as subtraction.

Then he found Jony Ive.

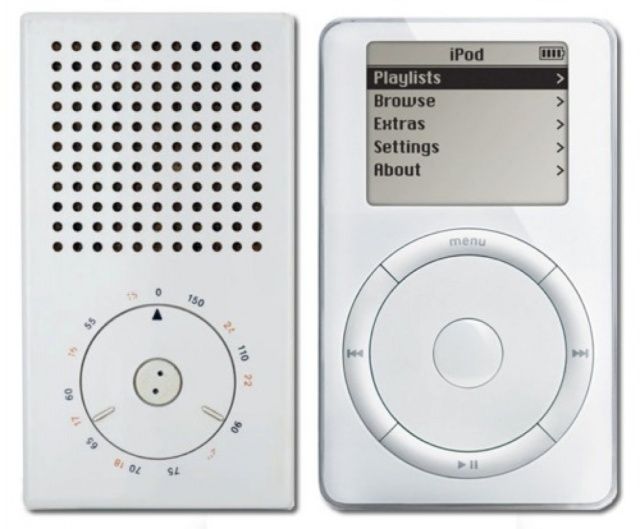

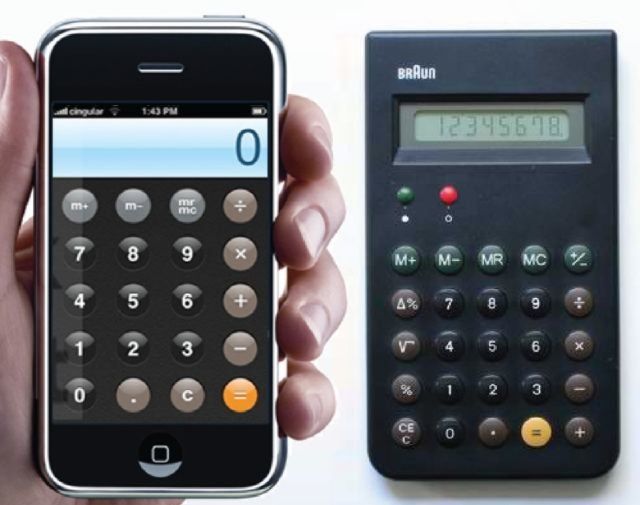

Ive’s design philosophy came directly from Dieter Rams at Braun. Rams’ principle was “less, but better.” Look at a Braun T3 pocket radio from the 1960s and then look at the original iPod. The lineage is obvious.

Jobs once said: “If I had a spiritual partner at Apple, it’s Jony.” What made the partnership work wasn’t that both had good aesthetic sense. It was that both understood deep simplicity versus shallow simplicity. Shallow simplicity is removing features to make something look clean. Deep simplicity is rethinking the problem until the complex thing becomes genuinely simple. The iPod’s scroll wheel wasn’t simple because it had fewer buttons. It was simple because it was the right interface for navigating a thousand songs.

Taste is empathy plus conviction

Here’s a working definition: taste is empathy plus conviction.

Empathy means understanding what users actually need, which is often different from what they say they want. Conviction means having a strong, sometimes contrarian, vision for where things should go and being willing to make unpopular decisions to get there.

Jobs removed the floppy drive from the iMac in 1998. People were furious. He was right. Apple removed the headphone jack from the iPhone in 2016. People were furious. They were right. These decisions required both understanding where users were headed (empathy) and being willing to take the hit for getting there early (conviction).

Taste is judgment, not design skill. You don’t need to be able to draw a pixel-perfect mockup. You need to be able to look at a product and know whether it’s right.

What bad taste looks like

Taste is easier to understand through its absence.

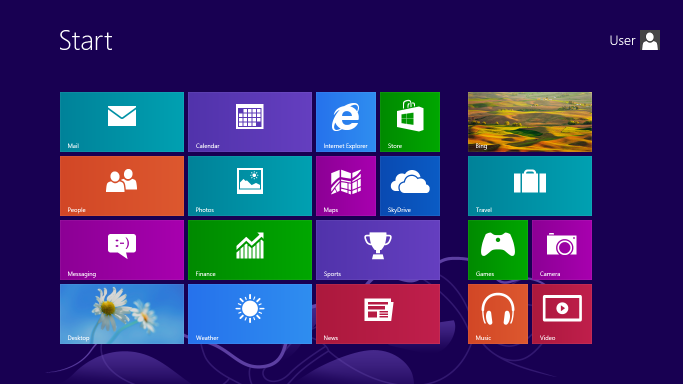

Windows 8 (2012). Microsoft saw the tablet wave coming and decided the answer was to force a touch-first interface onto desktop users. The Metro UI was bold, visually distinctive, and deeply wrong for anyone using a mouse and keyboard. They had conviction (the future is touch) but no empathy (most of your users are sitting at desks). The Start screen looked great in demos. In practice, people couldn’t find their programs. It was conviction without empathy.

Amazon Fire Phone (2014). Jeff Bezos reportedly drove the design process personally. The headline feature was “Dynamic Perspective,” a gimmicky 3D effect that used four front-facing cameras to track your face. It solved no real problem. The phone was built to serve Amazon’s shopping ecosystem, not the user’s needs. It was dead within a year, and Amazon wrote off $170 million. Conviction (we should own mobile commerce) without empathy (nobody asked for 3D head-tracking).

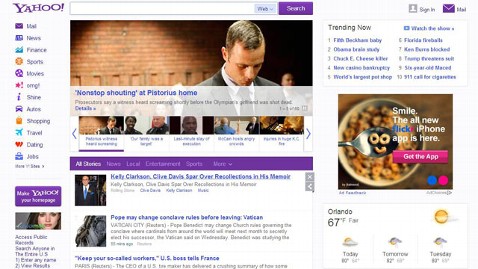

Yahoo’s 2013 redesign. Marissa Mayer overrode her design team to push through a logo and product redesign that borrowed Apple’s visual language without understanding Apple’s underlying principles. The result felt like a costume, not a transformation. Yahoo lost 28% of its search traffic that year. This was the inverse problem: neither conviction nor empathy, just imitation.

Taste in code

Taste isn’t limited to product design. It shows up in code, system architecture, API design.

It’s knowing when to reach for a simple solution versus a scalable one. When to abstract and when to keep things concrete. When a system “feels right” versus when it works but will become a maintenance nightmare in six months. Good engineering taste means building things that other people can understand, extend, and debug without wanting to rewrite everything.

This kind of taste is hard to develop without hands-on experience. You build it by reading other people’s code, shipping things that break, refactoring your own mistakes. The pattern recognition comes from doing.

Which raises the question for AI-assisted development: can you cultivate engineering taste if you’re not writing the code yourself? I explored this more in my post about junior developers and AI. The short version: I’m not sure, and nobody else seems sure either.

Taste has always been the meta

Taste isn’t new. It always separated great products from good ones, great engineers from competent ones, great companies from forgettable ones. The Rams/Ive lineage goes back to the 1960s. Jobs was talking about taste before most people had internet access.

What’s changed is that AI has collapsed the cost of building. That doesn’t give anyone taste. If anything, it widens the gap. When building is cheap, the world gets flooded with things that work but don’t matter. The things that stand out are the ones where someone cared enough to get the details right, to leave the unnecessary parts out, to make it feel like it was made for you.

Taste is cultivated through exposure, through mistakes, through caring deeply about the work. None of that has changed. None of it ever will.

The people who think taste just became important weren’t paying attention.